Gender reassignment surgery

Cirugía para la reasignación sexual

Mauricio Baley-Spindel1*, Daniel Martínez-Cabrera2, Isaac Baley-Spindel1, Erick Moreno-Pizarro3, and Aarón E. Serrano-Padilla3

1Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon, ABC Medical Center, Mexico City; 2Psychiatry Resident, Centro Medico Nacional “20 de Noviembre,” Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado (ISSSTE), Mexico City; 3Departamento de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad de Guanajuato,Guanajuato. Mexico

*Correspondence: Mauricio Baley-Spindel. E-mail: mauriciobaleys@gmail.com

Abstract

Gender variance is a term used to describe behaviors, appearances, expressions, or identities of a person that does not conform to the cultural norms expected of their biological sex. Gender reassignment surgery is a constantly evolving procedure that involves psychosocial aspects for patients who request it. These patients, experiencing discomfort due to gender identity variations, require multidisciplinary evaluations that cover esthetic, medical, psychological, and social aspects for proper management. In this paper, we aim to provide a narrative review of gender variance, focusing on the surgical treatments and approaches carried out in the transition process.

Keywords: Plastic surgery. Sexual reassignment. Transgender.

Resumen

La variación de género es un término utilizado para describir aquellas conductas, apariencias, expresiones o la identidad de una persona que no se conforma con las normas culturales esperadas de su sexo biológico. La cirugía de reasignación de género, es un procedimiento que se encuentra en constante actualización, y que involucra aspectos psicosociales para los pacientes que la solicitan. Estos, al encontrarse con variaciones en la identidad de genero que causan molestia y disconfort, requieren valoraciones multidisciplinarias que abarquen los aspectos estéticos, médicos, psicológicos y sociales para su correcto abordaje. En el presente trabajo pretendemos hacer una revisión narrativa de la variación de género, enfocándonos en los tratamientos y abordajes quirúrgicos que se llevan a cabo en el proceso de transición.

Palabras clave: Cirugía plástica. Reasignación sexual. Transgénero.

Introduction

Gender variance is a term used to describe behaviors, appearances, expressions, or identities of a person that does not conform to the cultural norms expected of their biological sex1. Within the concepts that explain human sexuality, there are biological sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression. Sexual expression is multifaceted and presents considerable fluidity, and it is not dichotomous.

The inconsistency between physical phenotype and gender is known as gender dysphoria, defined by Stoller as “the conviction of a biologically normal subject to belong to the opposite sex.” Becerra adds to the definition that there is dissatisfaction toward primary and secondary sexual characteristics, as well as a constant desire to change them toward the gender with which the individual identifies. This feeling of discomfort can lead to surgical or pharmacological modification of the physical phenotype to adapt it to the individual’s gender identification. This phenomenon is known as transsexuality1-3.

Background

Transsexuality and gender variance are conditions that have existed since ancient times. The first description in scientific literature dates back to 1869, by Westphal, who defined it as “contrary sexual feeling.” In 1894, Krafft-Ebbing described dressing in the opposite sex as a “paranoid sexual metamorphosis.” In 1916, Marcuse called it “psychosexual inversion.” In the early 1930s, Abraham described the first patient who had undergone anatomical changes4,5.

Endocrinologist Harry Benjamin coined the term “transsexuality” in 1966. Three years later, endocrinologist John Monet coined the concept of “Gender Reassignment.” In 1979, the International Gender Dysphoria Association “Harry Benjamin,” currently known as the “World Professional Association for Transgender Health,” issued the last revision of management guidelines in 20014-6.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of gender dysphoria and related sexual disorders is uncertain due to the lack of formal epidemiological studies on the topic4-7. According to DSM-5 reports, the prevalence of gender dysphoria ranges from 0.005 to 0.014% in biological males and from 0.002 to 0.003% in biological females7.

Various studies report a higher prevalence in trans women than in trans men, earlier age of onset in trans women, and a higher incidence of homosexual orientation in trans men than in trans women8,9.

In a study by Fagot (1977), of a group of 106 children, seven (6.6%) showed references to cross-gender preferences, while in a group of 101 girls, five (4.9%) showed such references10-12.

Gender dysphoria is more common in boys than in girls, with a ratio of 5.75:1 in children, and 2.93:1 in adolescents11,12.

Comorbidities

In patients with gender dysphoria, the presence of a psychiatric disorder has been reported in up to 30.9% of cases13-15.

Regarding axis I comorbidities, up to 70% of all reported psychiatric comorbidities have been reported, of which 60% have been referred to affective disorders and 28% to anxiety spectrum disorders. These disorders can lead to self-harm behavior (28.8-41%) and are up to 8.6 times more likely to result in suicidal behavior or attempts (17.5-4.2% in suicidal ideation and 15.8% in suicide attempts). Dissociative symptoms have also been described as highly prevalent (29.6%), as well as personality disorders, with a total prevalence of up to 15%. Schizoid, avoidant, and borderline personality disorders, with 5, 4, and 7%, respectively, were the most common. It has been found that being a gender-incongruent child is a risk factor for physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. They have the highest levels of posttraumatic stress and very high rates of suicide and suicide attempts, as well as a higher level of rejection by their peers (transphobia, bullying) 56%16-18. Table 1 shows the most prevalent psychiatric comorbidities.

Table 1. Psychiatric comorbidities

| Mental disorder | Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Any psychiatric disorder | 30.9% |

| Affective disorders | 60% |

| Anxiety disorders | 28% |

| Dissociative | 29.6% |

| Psychotic | 1.4% |

| Suicidal | 42% |

| Autism | 11.5% |

| Personality disorders | 4.3% |

| Substance use | 3.6% |

Adapted from: Aitken et al., 2016; Colizzi et al., 2015.

Etiology

To talk about the genesis of gender dysphoria, we must discuss gender expression variation, which encompasses biological, psychological, and social factors. Psychological theories focus on the cognitive development of the child and how they construct the concept of “gender” as development progresses. At 2.5-years-old, they learn to differentiate between the faces of a man and a woman; from 2 to 4-years-old, they identify the differences between the pronouns “he” and “she.” At this age, most children start playing games that correspond to their biological sex. Gender segregation begins when they start preschool, preferring playmates of the same sex. Gender vision becomes more constant from the age of six19.

Experimental studies have identified some biological and environmental factors as contributors to the genesis of gender expression variation, such as dysregulation of sex hormone levels in prenatal and perinatal stages, which are determinants for determining the conformation of various neural networks, favoring the “feminization” or “masculinization” of the central nervous system20,21.

Genetics

The expression of various polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor (ER) has been described in transgender women. Once the ligand (estrogen) binds to the receptor, it undergoes a change in its structure, resulting in the activation of specific DNA regions for the activation of certain transcription factors. Case-control studies on the polymorphism expression of ER-α subunits describe the ER-α XbaI-rs9340799 polymorphism, which expresses a significant difference between transgender men and cisgender men but is not found in transgender women with their cis controls.20,21 It is inferred that this variation in the (A/G) polymorphism favors cerebral feminization, being more frequently expressed in cisgender women, but not in transgender men. Likewise, a high number of repetitions in the ER-α subunit promotes cerebral “defeminization”21. Genetic variations in enzymes that metabolize sex steroids, such as CYP17 A2, result in lower biological activity, resulting in higher concentrations in the cortex during neurodevelopment, and have been observed more frequently in transgender men and less frequently in biological and transgender women21.

Fetal imaging studies and, more recently, functional magnetic resonance imaging studies examining interactions between different brain areas (functional connectivity) have been conducted. These studies specifically found brain regions such as the middle prefrontal cortex, anterior insula, temporoparietal junction, precuneus, and specific neural networks associated with the formation of body self-perception and self-referential thinking. Alterations in functional connectivity have been found in transgender men and women and could explain the difference in gender self-perception20,21.

Review of the anatomy

Male sexual organs

The penis is the male organ involved in both urinary and sexual functions. It is a cylindrical organ that hangs below the pubic symphysis, above the scrotal sacs. Its size and consistency vary depending on whether it is in a flaccid or erect state—when flaccid, it measures approximately 8-10 cm, and in erection, it becomes rigid and measures approximately 14-22 cm22-25.

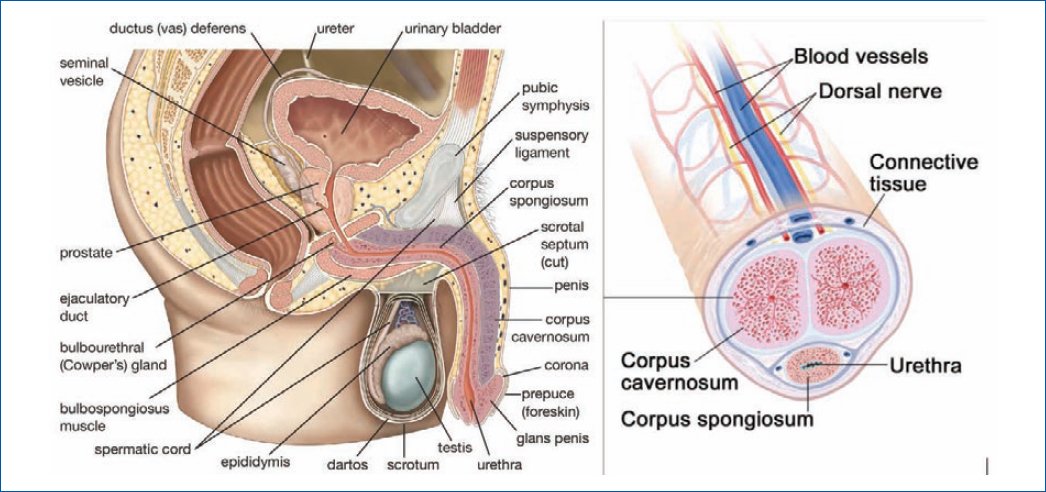

It consists of a root, a body, and the glans. The root of the penis is the inserted portion, located in the superficial perineal pouch, and consists of the pillars, the bulb (containing erectile tissue), and the ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus muscles. The body of the penis is the free, pendulous part of the penis in the flaccid state and lacks muscles. The penis is composed of three cylindrical bodies of erectile cavernous tissue—two cavernous bodies and one spongy body, surrounded by a fibrous capsule called the tunica albuginea (Fig. 1)22-25.

Figure 1. Anatomical reminder of male sexual organs. Britannica, the editors of the encyclopedia “penis,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 29 March 2023.

More superficial to this capsule is the deep fascia of the penis (Buck’s fascia), which is an elastic fascia that forms a robust membranous covering for the cavernous bodies and the spongy body, uniting them together. It is followed by the more superficial layer of loose areolar tissue, which terminates in the skin.

The cavernous bodies constitute most of the penis and originate at the ischiopubic branches. They contain erectile tissue, which has arteries, nerves, nerve fibers, and venous sinuses.

The spongy body is located in the ventral groove, between the two cavernous bodies, and contains the spongy urethra. It expands distally to form the glans, which in turn forms the head of the penis. The margin of the glans projects beyond the ends of the cavernous bodies, forming the corona. This corona surpasses a constriction zone with an oblique groove called the neck of the glans, which separates the glans from the body of the penis. One of the functions of the spongy body is to prevent compression of the urethra during erection.

The penile stability is aided by ligaments such as the suspensory ligament of the penis, which arises from the anterior surface of the pubic symphysis, and the fundiform ligament of the penis, which extends from the linea alba above the pubic symphysis and divides to encircle the penis before inserting into its fascia26,27.

The blood supply to the penis is mainly provided by the internal pudendal artery. The terminal portion of this artery divides into three branches—the bulbourethral artery, the dorsal artery, and the cavernous artery (deep artery). The cavernous artery supplies blood to the cavernous bodies, the dorsal to the glans of the penis, and the bulbourethral to the spongy body.

Venous and lymphatic drainage of the penis occurs as follows—the blood from the cavernous spaces drains into a venous plexus that joins the deep dorsal vein of the penis in the deep fascia. This vein passes deep into the pubic arch and joins the prostatic venous plexus. Blood from the superficial coverings of the penis drains into the superficial dorsal vein, which empties into the superficial external pudendal vein. The superficial inguinal lymph nodes receive most of the lymph from the penis.

Sympathetic innervation is provided by fibers of the lumbar and sacral splanchnic nerves that reach the inferior hypogastric plexuses, where they make synapses. Parasympathetic innervation comes from the pelvic splanchnic nerves, whose fibers pass through the inferior hypogastric plexuses. From these plexuses, the cavernous nerves of the penis emerge, carrying vegetative fibers of both types to the bodies. Sensory innervation is provided by the genital branches of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves (from the lumbar plexus), which sensitively innervate the skin of the most anterior part of the scrotum. The pudendal nerve (from the sacral plexus) is the most relevant27.

Female sexual organs

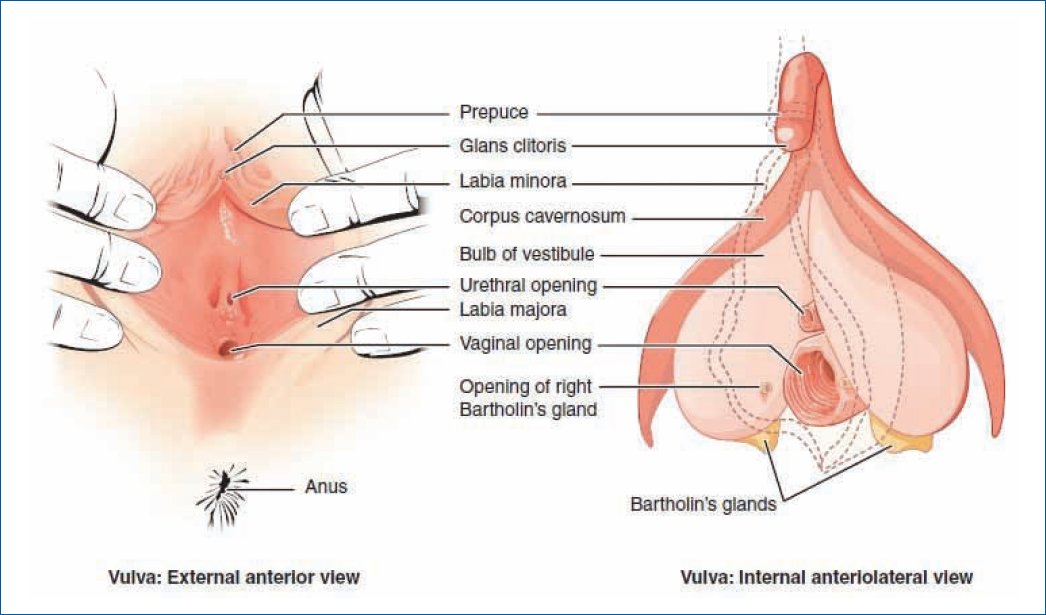

The vagina is a muscular-membranous tube that extends from the cervix to the vaginal vestibule. The upper end surrounds the cervix, while the lower end passes anteroinferiorly through the pelvic floor to open into the vestibule.

The vagina pierces the perineal membrane. Normally it is collapsed except at the lower end where the cervix keeps it open, and it is here where the anterior, posterior, and lateral portions are described. The deepest portion is the posterior part of the cul-de-sac, which is intimately related to the rectouterine cul-de-sac. This part is very distensible and allows the accommodation of the erect penis.

Four muscles compress the vagina and act as sphincters—the pubovaginal muscle, the external urethral sphincter, the urethrovaginal sphincter, and the bulbospongiosus muscle.

The relationships of the vagina are anterior, the base of the bladder and the urethra; laterally, the levator ani muscle, the visceral pelvic fascia, and the ureters; posteriorly, the anal canal, the rectum, and the rectouterine cul-de-sac.

To discuss vaginal vasculature, we divide it into two portions:

-Upper portion: through the uterine arteries, which arise from the internal iliac artery.

-Middle and lower portion: through the vaginal arteries that derive from the middle rectal artery and the internal pudendal artery.

-Veins form vaginal venous plexuses along the lateral walls of the vagina and within the vaginal mucosa. They communicate with the vesical, uterine, and rectal venous plexuses and drain into the internal iliac veins27-28.

Innervation is derived from the uterovaginal plexus located with the uterine artery between the layers of the broad ligament of the uterus. The uterovaginal plexus is an extension of the inferior hypogastric plexus. Only 20-25% of the lower vagina is somatic in terms of innervation. The innervation of this lower portion is from the deep perineal branch of the pudendal nerve. Only this part of the vagina with somatic sympathetic innervation is sensitive to touch and temperature (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Anatomical reminder of female sexual organs. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-ap2/chapter/ anatomy-and-physiology-of-the-female-reproductive-system/

Gender reassignment

Gender dysphoria is characterized by a marked discrepancy between birth sex and gender identity, and is associated with immense emotional and physical stress. While many transgender individuals are able to achieve their gender identity without surgical interventions, a significant portion of the population seeks gender affirmation through surgery29-32.

The desired surgeries are taken as the standard of treatment.

This condition was described and recognized in 1950 by the American psychiatrist Harry Benjamin, who formalized the diagnostic criteria for transsexualism in 196633-35.

First phase

Diagnosis

The term transgender is not a formal diagnosis. When it causes concern, insecurity, and questions about their gender identity, which persists during their development and becomes the most important aspect of their life, or prevents the establishment of gender identity without conflicts, they have passed a clinical limit.

When these individuals meet the criteria in one of the two official nomenclatures such as the International Classification of Diseases ICD-10 or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, it is diagnosed as a Gender Identity Disorder35-39 (review supplementary data, where you will find: Table 2. DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Gender Dysphoria, and Table 3. ICD-10 Diagnostic Criteria for Gender Identity Disorders).

Table 2. Criterios diagnósticos del DSM-5 para disforia de género

| Diagnostic | Diagnostic criteria |

|---|---|

Gender dysphoria in children |

A marked incongruence between one’s desire or expressed sex and one’s assigned sex, of a minimum duration of six months, manifested by at least six of the following characteristics (one of which must be Criterion A1): A powerful desire to be of the other sex or an insistence that he or she is of the opposite sex. In boys (assigned sex), a strong preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; in girls (assigned sex) a strong preference for wearing only typically masculine clothing and a strong resistance to wearing typically female clothing. Marked and persistent preferences for the role of the other sex or fantasies regarding belonging to the other sex. A marked preference for toys, games, or activities commonly used or practiced by the opposite sex. A marked preference for playmates of the opposite sex. In boys (assigned sex), a strong rejection of typically masculine toys, games, and activities, as well as a marked avoidance of horseplay; A marked disgust with one’s own sexual anatomy. A strong desire to possess both primary and secondary sexual characteristics corresponds to the sex that is the desire. The problem is associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, school, or other important areas of functioning. Specify if—with a disorder of sexual development. |

Gender dysphoria in adolescents and adults. |

A marked incongruence between one’s desire or expressed sex and the one assigned to oneself, of a minimum duration of six months, manifested by a minimum of two of the following characteristics: A marked incongruity between the sex one feels or expresses and his primary or secondary sexual characters. A strong desire to get rid of one’s primary or secondary sexual characteristics, because of a marked incongruity with the sex that is desired or expressed. A strong desire to possess sexual characteristics, both primary and secondary, corresponding to the opposite sex. A strong desire to be the other sex (or alternate sex other than the one assigned to you). A strong desire to be treated as the opposite sex (or an alternate sex other than the one assigned to you). A strong conviction that one has the typical feelings and reactions of the other sex. The problem is associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Specify if—with a disorder of sexual development. Posttransition. |

Adapted from: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.; 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053.

Table 3. ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for gender identity disorders

| Condition | Description |

| F64.0 transsexualism | Desire to live and to be accepted as a member of the opposite sex is usually accompanied by a feeling of discomfort or inadequacy to one’s anatomical sex, and the desire to undergo surgery and hormone treatment to make one’s body as congruent as possible with the person’s preferred sex. |

| F64.1 dual role transvestite | Wearing clothing of the opposite sex during a stage of life to enjoy the transient experience of being a member of that sex, but without any desire for a more permanent sex change or surgical reassignment, and without accompanying sexual arousal. dressing in clothes of the opposite sex. |

| F64.2 gender identity disorder in childhood | A disorder whose first manifestation usually occurs during early childhood (always, well before puberty), which is characterized by intense and permanent anxiety in relation to one’s own sex, together with the desire to belong to the other sex or with the insistence that it belongs to him. There is a persistent preoccupation with clothing and activities of the opposite sex and disowning of the same sex. To make this normal diagnosis. Just masculine habits in girls or effeminate behavior in boys are not enough. |

Adapted from: Organización Mundial de la Salud. Guía de Bolsillo de La Clasificción CIE-10: Clasificación de Los Trastornos Mentales y Del Comportamiento.; 2000. doi:9788479034924

Second phase

Hormone therapy

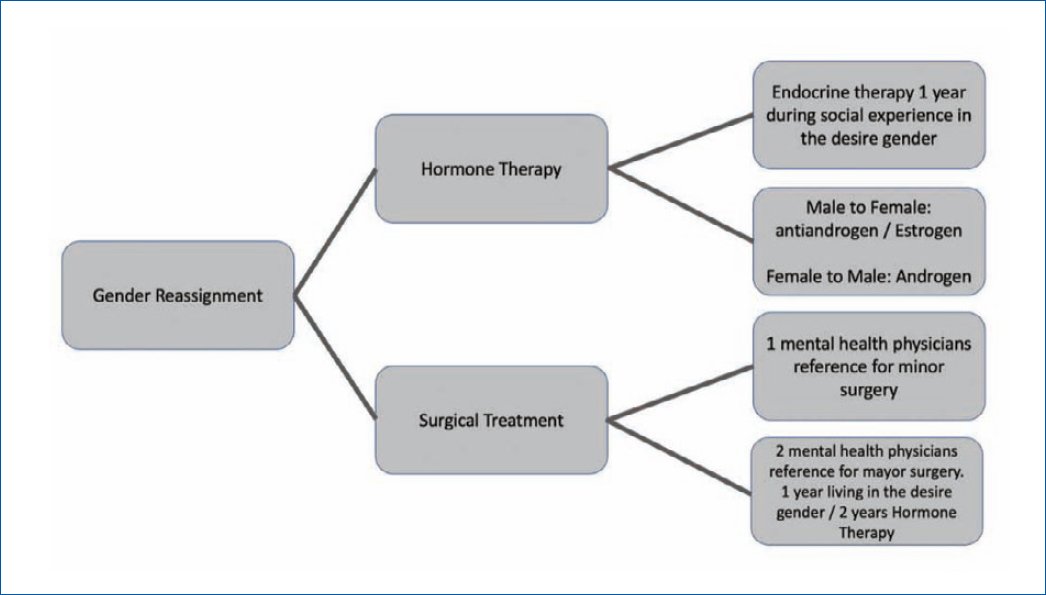

At the end of the first phase, the diagnosis phase, the patient is referred to a physician who is responsible for hormone therapy.

Hormone therapy varies, and the surgeon should be familiar with the side effects of this therapy and how it relates to surgical treatment. This includes problems with liver function, risk of venous thromboembolism, electrolyte imbalance, and drug interactions.

The goals of endocrine therapy are to change the secondary characteristics of gender. This therapy is typically individualized to the patient’s needs and desires based on their goals, associated conditions, and social and economic considerations40-42.

Feminization is achieved through two mechanisms; suppression of androgen effects and induction of female physical characteristics. Androgen suppression is achieved through medications that suppress gonadotropin-releasing hormones or are antagonists of this hormone. Estrogens are used to induce female physical sexual characteristics, and their mechanism of action is through direct stimulation of tissue receptors.

Masculinization is achieved by following the principles of hormone replacement for patients with hypogonadism. Both parenteral and dermal preparations are available to achieve this goal40-42.

Third phase

Surgical treatment

Once the surgeon is satisfied with the diagnosis and hormonal treatment has been established, preoperative evaluation is performed. Surgical options43,44.

Male to female

Main options:

-Penile disassembly and inversion vaginoplasty

-Intestinal transplant

Penile disassembly and inversion vaginoplasty

Vaginoplasty is the most common surgery, it involves penile disassembly and inversion with an anterior pedicle flap base. Although a wide variety of modifications to the technique have been described in the literature, the penile disassembly and inversion technique uses penile skin and subsequently a perineal scrotal flap to construct the vaginal cavity45,46.

Intestinal transposition

Typically reserved for revision cases, although in some centers it is the first-line treatment.

Advantages of this procedure:

Creation of a vascularized vagina of 12-15 cm, providing sufficient vaginal depth, as well as adequate lubrication and less shrinkage.

Disadvantages of this procedure:

Intraabdominal surgery and intestinal anastomosis are necessary.

Indications for intestinal transposition:

Penile hypoplasia. Failed primary vaginoplasty can also be used in women with congenital absence of the vagina or dysfunctional vagina.

Contraindications:

Intestinal malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and extensive abdominal surgery34,35,37,38,46.

Female-to-male

According to Hage and DeGraaf, the ideal neophallus should be created in a single procedure, be aesthetically appropriate, produce a tactile and erogenous sensation, have a functional neourethra, and allow for standing urination.

Although there is no single procedure that meets all these requirements, there are a variety of techniques for constructing an aesthetic and functional neophallus.

Metoidioplasty

This involves creating a neophallus from a hypertrophied clitoris.

The advantages of metoidioplasty include reconstruction with similar glands, a tactile and erogenous sensation provided by clitoral tissue, sustained and rigid erections without the use of prosthetics, a smaller donor site scar, and shorter hospitalization and operative times, making it cheaper than other techniques.

Compared to other techniques, the resulting penis from this technique is shorter, approximately 5-7 cm, which can result in compromised sexual function, difficulty penetration, and difficulty urinating while standing.

Complications range from 14 to 37%, which are generally minor and related to urethroplasty47–50.

Phalloplasty with locoregional flap

Phalloplasty with a pedicled Anterolateral Thigh Perforator Flap (ALT flap) has been taken as the flap of choice. In this procedure, the flap is tabularized and passed through an inguinal tunnel for neophallus creation.

Advantages of this flap include safe vascularity, reduced risk of total flap failure, discreet donor site, and the ability for reinnervation by cutaneous femoral nerves.

Disadvantage—obese or overweight patients have a thick subcutaneous tissue layer, making it more difficult to create the neourethra47–50.

Radial forearm flap

It is the workhorse, the design is significantly larger than with other flaps and can be modified in several ways. It can be included as osteocutaneous in a single procedure, which allows for a more reliable erection. The anatomy is constant with a long pedicle, thin fat and skin, and has a better esthetic appearance.

They have good sensation, sexual satisfaction, and the ability to the placement of a prosthesis.

Disadvantages—morbidity of the donor site. The scar on the arm has been stigmatized as a “signature” of this procedure.

The most frequent complication is related to the neourethra with the appearance of fistulas and is more problematic (Fig. 3)34,35,47-50.

Figure 3. Treatment of gender dysphoria.

Conclusion

Gender dysphoria is a complex entity and as such deserves special attention. Primarily, due to the difficulty of its approach and management, which at all times must be multidisciplinary and address the medical and social needs that may arise. Healthcare professionals must be trained and knowledgeable about the best alternatives to provide the necessary support to these vulnerable groups, in order to improve their quality of life and act ethically in favor of the interests of patients seeking relief from feelings of distress.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Use of artificial intelligence for generating text. The authors declare that they have not used any type of generative artificial intelligence for the writing of this manuscript, nor for the creation of images, graphics, tables, or their corresponding captions.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at DOI: 10.24875/AMH.M23000035. These data are provided by the corresponding author and published online for the benefit of the reader. The contents of supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

References

1. Bonifacio HJ, Rosenthal SM. Gender variance and dysphoria in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62:1001-16.

2. Rodríguez MF, Granda MM, González V. Gender incongruence is no longer a mental disorder. J Ment Health Clin Psychol. 2018;2:6-8.

3. Byne W, Karasic DH, Coleman E, Eyler AE, Kidd JD,

Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, et al. Gender dysphoria in adults: an overview and primer for psychiatrists. Transgend Health. 2018;3:57-A3.

4. Capetillo-Ventura NC, Jalil-Pérez SI, Motilla-Negrete K. Gender dysphoria: an overview. Med Univ. 2015;17:53-8.

5. Beek TF, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Kreukels BPC. Gender incongruence/gender dysphoria and its classification history. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28:5-12.

6. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7 Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165-32.

7. Sadock VA, Sadock BJ, Ruiz P. Synopsis of psychiatry behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry, eleventh edition. baltimore, MD: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015.

8. Aitken M, VanderLaan DP, Wasserman L, Stojanovski S, Zucker KJ. Self-harm and suicidality in children referred for gender dysphoria J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:513-20.

9. Bizic MR, Jeftovic M, Pusica S, Stojanovic B, Duisin D, Vujovic S, et al. Gender dysphoria: bioethical aspects of medical treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9652305.

10. Aitken M, Steensma TD, Blanchard R, VanderLaan DP, Wood H,

Fuentes A, et al. Evidence for an altered sex ratio in clinic-referred adolescents with gender dysphoria. J Sex Med. 2015;12:756-63.

11. Hilden M, Glintborg D, Andersen MS, Kyster N, Rasmussen SC,

Tolstrup A, et al. Gender incongruence in Denmark, a quantitative assessment. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1800-5.

12. Zucker KJ, Lawrence AA. Epidemiology of gender identity disorder: Recommendations for the standards of care of the world professional association for transgender health. Int J Transgenderism. 2009;11:8-18.

13. Claahsen-van der Grinten H, Verhaak C, Steensma T, Middelberg T, Roeffen J, Klink D. Gender incongruence and gender dysphoria in childhood and adolescence-current insights in diagnostics, management, and follow-up. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:1349-57.

14. Heylens G, Elaut E, Kreukels BPC, Paap MC, Cerwenka S,

Richter-Appelt H, et al. Psychiatric characteristics in transsexual individuals: multicentre study in four European countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:151-6.

15. Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, de Blok CJM, Klaver M, de Vries ALC,

Wensing-Kruger SA, et al. The Amsterdam cohort of gender dysphoria study (1972-2015): trends in prevalence, treatment, and regrets. J Sex Med. 2018;15:582-90.

16. Cohen-Kettenis PT, Klink D. Adolescents with gender dysphoria. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;29:485-95.

17. Moore KL, Dalley AF II, Agur A. Anatomia con orientacion clinica. 8th ed. la Ciudad Condal, España: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2018.

18. Shah M, DeSilva A. The male genitalia: The role of the narrator in psychiatric notes, 1890-1990, v. 2, first series. London, England: Radcliffe Publishing; 2007.

19. Colizzi M, Costa R, Todarello O. Dissociative symptoms in individuals with gender dysphoria: Is the elevated prevalence real? Psychiatry Res. 2015;226:173-80.

20. Uribe C, Junque C, Gómez-Gil E,Abos A, Mueller SC, Guillamon A. Brain network interactions in transgender individuals with gender incongruence. Neuroimage. 2020;211:116613.

21. Hamidi O, Nippoldt TB. Biology of gender identity and gender incongruence. In: transgender medicine. Cham:Springer International Publishing; 2019:39-50.

22. Martins FE, Kulkarni SB, Köhler TS. Textbook of Male Genitourethral Reconstruction. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020.

23. Gabrielson AT, Le TV, Fontenot C, Usta M, Hellstrom WJG. Male genital dermatology: a primer for the sexual medicine physician. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7:71-83.

24. Netter FH. Atlas de Anatomia Humana. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2019.

25. Lu MD MDiv S. Sex Reassignment Surgery: Is It Good for Patients? 2018.

26. SnellL, Cordeiro P, Pusic A. Reconstruction of acquired vaginal defects. Trunk surgery Nelligan. 4.

27. Serati M, Salvatore S, Rizk D. Female genital cosmetic surgery: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1411-2.

28. Dobbeleir J, Landuyt KV, Monstrey SJ. Aesthetic surgery of the female genitalia. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25:130-41.

29. Schechter L. Surgical management of the transgender patient. Philadelphia, PA, United States of America: Elsevier - Health Sciences Division; 2016.

30. Cunha Rodrigues GNV, Parada BAC, Caetano PAS. Postoperative Follow-up In Male-To-Female Sexual Reassignment Surgery: A Self-Reported Functional And Psychosocial Assessment. Coimbra, Portugal: Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra; 2020.

31. Schechter LS, Surgery for gender dysphoria. Trunk Surgery. Plastic Surgery Neligan. 2018.

32. Monstrey S, Hoebeke P, Dhont M, De Cuypere G, Rubens R,

Moerman M, et al. Surgical therapy in transsexual patients: a multi-disciplinary approach. Acta Chir Belg. 2001;101:200-9.

33. Lozano-Verduzco I, Melendez R. Transgender individuals in Mexico: exploring characteristics and experiences of discrimination and violence. Psychol Sex. 2021;12:235-47.

34. Wirthmann A, Majenka P, Kaufmann M, Wellenbrock S, Kasper L, et al. Phalloplasty in female-to-male transsexuals by Gottlieb and Levine’s free radial forearm flap technique-a long-term single-center experience over more than two decades. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2018;34:235-41.

35. Ettner R, Monstrey S, Coleman E, eds. Principles of transgender medicine and surgery: 2nd ed.London, England: Routledge; 2016.

36. Milrod C. How young is too young: ethical concerns in genital surgery of the transgender MTF adolescent. J Sex Med. 2014;11:338-46.

37. Kailas M, Lu HMS, Rothman EF, Safer JD. Prevalence and types of gender-affirming surgery among a sample of transgender endocrinology patients prior to state expansion of insurance coverage. Endocr Pract. 2017;23:780-6.

38. Morrison SD, Dy GW, Chong HJ, Holt SK, Vedder NB, Sorensen MD, et al. Transgender-related education in plastic surgery and urology residency programs J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:178-83.

39. El-Hadi H, Stone J, Temple-Oberle C, Harrop AR. Gender-affirming surgery for transgender individuals: perceived satisfaction and barriers to care. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2018;26:263-8.

40. Stowell JT, Grimstad FW, Kirkpatrick DL, Brown ER, Santucci RA,

Crane C, et al. Imaging findings in transgender patients after gender-affirming surgery Radiographics. 2019;39:1368-92.

41. Frederick MJ, Berhanu AE, Bartlett R. Chest surgery in female to male transgender individuals. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78:249-53.

42. Mahfouda S, Moore JK, Siafarikas A, Hewitt T, Ganti U, Lin A, et al. Gender-affirming hormones and surgery in transgender children and adolescents Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:484-98.

43. Berli JU, Knudson G, Fraser L,Tangpricha V, Ettner R, Ettner FM, et al. What surgeons need to know about gender confirmation surgery when providing care for transgender individuals: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:394-0.

44. Aydin D, Buk LJ, Partoft S, Bonde C, Thomsen MV, Tos T. Transgender surgery in Denmark from 1994 to 2015: 20-year follow-up study. J Sex Med. 2016;13:720-5.

45. Nolan IT, Kuhner CJ, Dy GW. Demographic and temporal trends in transgender identities and gender confirming surgery. Transl Androl Urol. 2019;8:184-90.

46. Zurada A, Salandy S, Roberts W, Gielecki J, Schober J, Loukas M. The evolution of transgender surgery: evolution of transgender surgery. Clin Anat. 2018;31:878-86.

47. Colebunders B, Brondeel S, D’Arpa S, Hoebeke P, Monstrey S. An update on the surgical treatment for transgender patients. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5:103-9.

48. Weinforth G, Fakin R, Giovanoli P, Nuñez DG. Quality of life following male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:253-60.

49.Sadeghipour Meybodi S, Mazaheri Meybodi A. Quality of life, suicidal attempt and satisfaction in gender dysphoria individuals undergone sex reassignment surgery. Annals of RSCB. 2021;25:4608-14.

50. Olegário RL, Vitorino SMA. An overview of sex reassignment surgery. Rev Fac Ciênc Médicas Sorocaba. 2020;21:151-2.